So I came across this picture on Pinterest the other day:

The caption is, as with so many other things one can find on the Internet, utter bullshit, but it did make me curious. The picture itself is apparently real. In the first third of the 19th century, some graves were enclosed with an iron cage, called a ‘mortsafe,’ as a way to thwart graverobbers, who were far more prevalent in Victorian Britain than zombies and vampires.

Under the law prior to 1832, the only corpses which could be dissected were those of criminals who were hanged. Changes to laws in the 18th century widened the number of crimes deemed hanging offenses, arguably to increase the number of eligible corpses. Nevertheless, demand continued to increase with advances in medicine, and graverobbers, known as ‘Resurrectionists,’ helpfully stepped in to meet the demand. Prior to the 1830s, resurrectionists stole bodies from fresh graves and sold them to physicians. (Some more enterprising gentlemen went so far as to make their own fresh corpses. William Burke and William Hare allegedly murdered 16 people in Edinburgh from 1827-1828, selling the corpses to anatomist Robert Knox.)

The Anatomy Act of 1832 made the study of anatomy respectable (sort of), and allowed researchers to use the unclaimed bodies of those who died in workhouses, hospitals, and prisons. Public anatomy museums popped up everywhere, giving ordinary people an opportunity to stare at skeletons, wax models of naked bodies, and pieces of bodies floating in jars. Titillating! In addition, the museums served as another way for physicians, as well as non-physicians, to study anatomy and learn more about diseases, without going to all the fuss of actually dissecting a body themselves. This very interesting article suggests that the Obscene Publications Act of 1857, which ultimately resulted in the closure of most of these museums, was actually orchestrated by the medical profession, and was “a strategy for creating a medical monopoly of anatomy by categorizing it as knowledge from which laypeople could be excluded on moral grounds.”

Notable Victorian Henry Gray, who legally obtained his research corpses from prisons and mortuaries, published Anatomy Descriptive and Surgical, the text that would eventually become Gray’s Anatomy, in 1858.

So, no there were no zombies in Victorian Britain. According to the OED, the word ‘Zombie’ actually derives from a South American term for a deity, and wasn’t used in Britain in the context we now know and love until 1900.

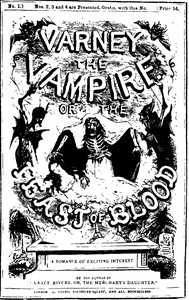

Vampires are another story altogether. Vampires have appeared in English literature since the mid-18th century, and I have to tell you, I find vampires fascinating.  The Victorians loved them too. Bram Stoker’s 1897 Dracula, of course, is the most famous, but before him there was Varney the Vampire, or the Feast of Blood. Published initially in 1845 in a series of 109 episodes in penny dreadfuls, Varney was ultimately released as a full length novel (rather more than that, actually–it is over 2,000 pages long) in 1847. Varney made vampires sexy–he had beautiful teeth and a mellifluous voice–and introduced many of the vampire tropes still in use today: fangs, hynoptic powers, and superhuman strength, although Sir Francis Varney doesn’t seem to mind garlic, can eat regular food (although he chooses not to), can walk in sunlight without either disintegrating or sparkling, and if killed or wounded, can be revived by the light of the full moon. Varney is terribly written, but oddly gripping–I downloaded a slightly abbreviated version to my Kindle and am probably going to have to go read it now. Perhaps we’ll discuss werewolfs at another time…

The Victorians loved them too. Bram Stoker’s 1897 Dracula, of course, is the most famous, but before him there was Varney the Vampire, or the Feast of Blood. Published initially in 1845 in a series of 109 episodes in penny dreadfuls, Varney was ultimately released as a full length novel (rather more than that, actually–it is over 2,000 pages long) in 1847. Varney made vampires sexy–he had beautiful teeth and a mellifluous voice–and introduced many of the vampire tropes still in use today: fangs, hynoptic powers, and superhuman strength, although Sir Francis Varney doesn’t seem to mind garlic, can eat regular food (although he chooses not to), can walk in sunlight without either disintegrating or sparkling, and if killed or wounded, can be revived by the light of the full moon. Varney is terribly written, but oddly gripping–I downloaded a slightly abbreviated version to my Kindle and am probably going to have to go read it now. Perhaps we’ll discuss werewolfs at another time…